Why Paganism Still Thrives in the Modern World

Understanding the Word “Pagan”

The word pagan comes from the Latin paganus, originally meaning “country dweller” or “villager.” In Roman times, it was a neutral word, used simply to describe someone who lived outside the cities. Over time, however, as Christianity spread, the term came to mean “those who clung to the old ways”—those who still worshipped their traditional gods and kept to their ancestral rituals. What began as a simple geographic label transformed into a religious one.

By the Middle Ages, “pagan” was often used as a derogatory term, meant to imply “heathen” or “idol worshiper.” Yet despite centuries of stigma, the word has been reclaimed in the modern era by practitioners who proudly identify as pagan. For them, the term is not an insult but an identity, one rooted in reverence for nature, ancient traditions, and diverse spiritual paths.

Ancient Pagan Roots

Paganism is not one religion but an umbrella term covering countless traditions. The ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Celts, Romans, Norse, and countless other cultures all practiced forms of what we now call paganism. Each had their own pantheon of gods, their own festivals, and their own sacred rites.

For example:

- The Celts celebrated festivals marking the cycles of the sun and the agricultural year, such as Beltane, Lughnasadh, Samhain, and Imbolc.

- The Norse honored gods like Odin, Thor, and Freyja through rituals, sacrifices, and seasonal festivals like Yule and Midsummer.

- The Romans celebrated Saturnalia, a festival of merriment, feasting, and role reversal that later influenced Christmas customs.

All of these cultures shared a worldview that saw the divine not as distant, abstract, and transcendent, but as immanent—woven into the earth, the seasons, and the lives of everyday people.

Paganism’s Disruption and Survival

With the rise of Christianity, many pagan traditions were suppressed, outlawed, or adapted into new religious frameworks. Temples were closed, sacred groves were cut down, and ancient rites were branded as dangerous or superstitious. Yet the old ways never truly disappeared. Folk traditions, seasonal celebrations, and ancestral customs survived in subtle forms, often blending with Christian festivals.

The Maypole dance of spring, the Yule log of winter, and even the custom of decorating evergreen trees all stem from pagan practices. Farmers continued to leave offerings for the spirits of the land. Midwives passed down herbal wisdom rooted in pagan healing traditions. Storytellers preserved the myths of gods and heroes.

In short, paganism adapted. It hid in plain sight. And in doing so, it survived the centuries.

The Modern Revival

By the 20th century, paganism began to re-emerge openly. Scholars of folklore and mythology published works that inspired seekers. Occult traditions like Theosophy and ceremonial magic drew attention back to ancient wisdom. In the 1950s, Gerald Gardner popularized Wicca, a modern form of pagan witchcraft that emphasized nature worship, magic, and reverence for both god and goddess.

Since then, paganism has grown steadily, becoming one of the fastest-expanding spiritual paths in Europe and North America. Today, practitioners can be found across the world, building communities both locally and online.

But the question remains: why has paganism thrived, even in the modern age of science, technology, and secularism? To answer this, we must look at the deeper appeal of the pagan worldview.

A Spirituality Rooted in Nature

One of the most powerful reasons paganism thrives today is its deep connection to nature. In a world where many of us live in cities, surrounded by concrete and technology, people feel an increasing disconnection from the Earth. The cycles of the seasons, once central to human life, have been overshadowed by artificial schedules and digital lives. Paganism offers a way back—a path to remembering that we are part of the living web of life.

The Wheel of the Year, a central concept for many modern pagans, reflects this connection. Eight festivals mark solstices, equinoxes, and the midpoints between them: Samhain, Yule, Imbolc, Ostara, Beltane, Litha, Lughnasadh, and Mabon. By celebrating these seasonal transitions, pagans reconnect with the land, the harvest, and the rhythms of the sun and moon.

This natural alignment appeals not only to spiritual seekers but also to those who care deeply about the environment. As climate change intensifies, honoring the Earth becomes not just a spiritual practice but an ethical responsibility. Pagan rituals often incorporate ecological action—tree planting, clean-up efforts, sustainable living—as sacred acts.

Personal Freedom and Spiritual Autonomy

Unlike many organized religions, paganism has no central authority, single sacred text, or rigid dogma. This lack of hierarchy is precisely what attracts modern practitioners. Paganism encourages individuals to seek their own relationship with the divine, whether through ritual, meditation, magic, or study of mythology.

This freedom allows for pluralism within paganism. Some pagans are polytheists, worshiping multiple gods and goddesses. Others are animists, seeing spirit in every rock, tree, and river. Some practice Wicca with structured rituals, while others follow reconstructionist paths, reviving ancient Norse, Hellenic, or Celtic traditions as faithfully as possible. Still others identify simply as eclectic pagans, blending practices from multiple traditions.

This diversity means that paganism is not a “one size fits all” faith. It’s a living tapestry of traditions, each practitioner weaving their own unique path. For modern spiritual seekers who value autonomy, this is deeply empowering.

The Rise of Eco-Spirituality

As the world faces unprecedented ecological challenges, paganism resonates with those seeking a spirituality that emphasizes harmony with the Earth. Many religions speak of humanity’s “dominion” over nature, but paganism stresses kinship. Humans are not separate from nature; we are nature. The rivers, forests, animals, and stars are kin, not resources to exploit.

This worldview fosters a sense of responsibility. To harm the Earth is to harm the divine. To honor the Earth is to honor the gods. In this sense, paganism offers not only spiritual meaning but also a framework for environmental activism. Many pagans today are active in ecological movements, seeing climate action as a sacred duty.

The Need for Community and Ritual

In modern life, many people feel isolated. Traditional community structures—extended families, local festivals, neighborhood gatherings—have eroded in favor of individualism and online interactions. Paganism, with its emphasis on seasonal festivals and communal rituals, fills this void.

Gathering with others to light a fire at solstice, drum under the full moon, or share food at harvest creates bonds that go deeper than casual socializing. These rituals provide a sense of belonging, not just to a community of people, but to the cosmos itself.

For solitary practitioners, ritual still offers grounding and connection. Even lighting a candle at the dark moon or making a simple offering of bread to the land spirits becomes a sacred act of participation in something larger than oneself.

Re-Enchantment in a Disenchanted World

Max Weber, a famous sociologist, once described the modern world as “disenchanted.” In our scientific, rationalist societies, the world is often seen as a machine—soulless, mechanical, predictable. While science offers many gifts, it also strips the world of wonder for those who seek more than data.

Paganism re-enchants the world. It invites us to see spirit in the wind, mystery in the stars, and divinity in the rivers. It doesn’t deny science but adds a layer of meaning that scientific analysis alone cannot provide. For many, this re-enchantment is profoundly healing, offering beauty and purpose in a time of growing existential anxiety.

Rituals and Ceremonies

At the heart of pagan practice are rituals—acts that bridge the material and the spiritual. These can be as simple as lighting incense or as elaborate as casting a ceremonial circle, calling the quarters, and invoking deities. What matters most is intention.

Rituals often align with natural cycles:

- Full moon ceremonies to honor the lunar goddess, seek insight, or perform magic.

- Seasonal festivals to celebrate the harvest, solstice, or equinox.

- Rites of passage marking birth, initiation, marriage (handfasting), and death.

Unlike dogmatic rituals found in some religions, pagan ceremonies are usually participatory, creative, and adaptable. A solitary practitioner might perform a short meditation under the stars, while a coven might gather in a forest for an elaborate seasonal celebration.

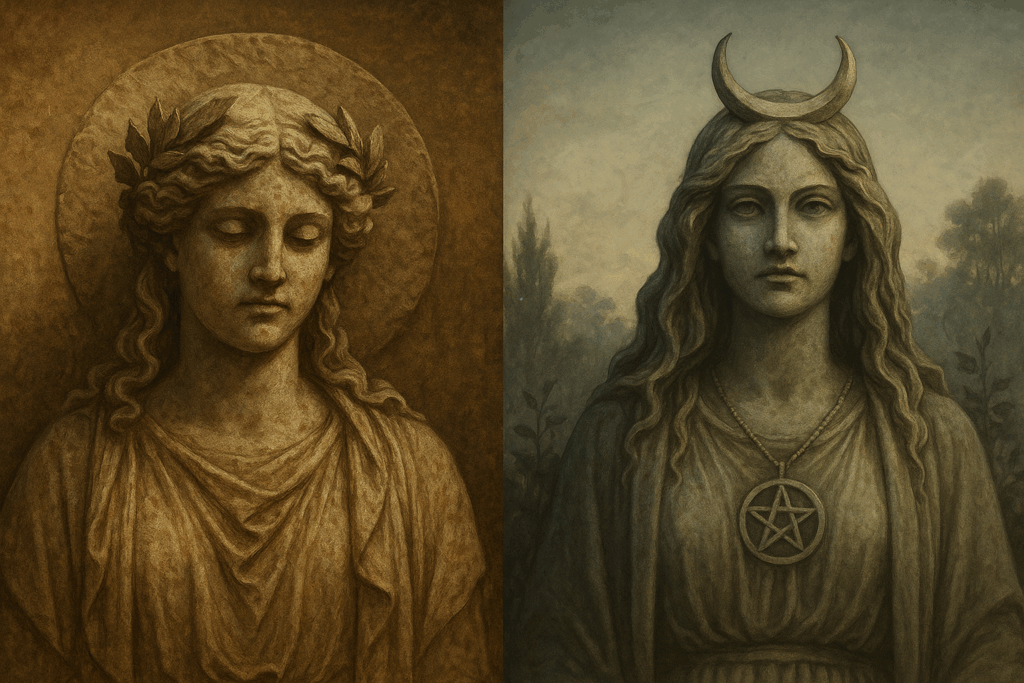

Honoring the Gods and Goddesses

Paganism is richly polytheistic. While monotheistic religions focus on one supreme deity, pagan traditions recognize many gods and goddesses, each embodying different aspects of life and nature.

Examples include:

- The Norse pantheon (Odin, Thor, Freyja, Frigg, Loki).

- The Greek pantheon (Zeus, Hera, Athena, Apollo, Artemis).

- The Celtic gods (The Dagda, Brigid, Lugh, The Morrigan).

- Egyptian deities (Isis, Osiris, Ra, Anubis, Hathor).

Many modern pagans view these deities as living beings, while others see them as archetypes—psychological symbols that help us understand aspects of the human experience. Either way, working with deities provides a sense of relationship, dialogue, and spiritual growth.

Magic and the Pagan Worldview

Magic is central to many pagan traditions, but not in the Hollywood sense of casting fireballs or flying on broomsticks. Pagan magic is about aligning with natural forces to bring about change, whether personal, communal, or environmental.

Forms of pagan magic include:

- Herbal magic: using plants for healing, protection, or ritual.

- Divination: tarot, runes, scrying, astrology.

- Candle magic: focusing intention through light and fire.

- Ritual offerings: giving thanks to gods, spirits, or ancestors.

Magic is not seen as “supernatural” but as part of the natural order. It’s the art of working with energies that are always present but often unnoticed.

The Role of Ancestors

In many pagan traditions, ancestors are revered as guides, protectors, and sources of wisdom. This practice is especially prominent during Samhain, when the veil between the living and the dead is believed to be thinnest. Pagans often build ancestor altars, leave offerings of food and drink, and share stories of those who came before.

Ancestor veneration is more than nostalgia—it acknowledges that we are the result of countless generations. Honoring them helps practitioners feel rooted in time and community, even when society feels disconnected.

Sacred Sites and Places of Power

Paganism is deeply tied to place. From Stonehenge to the sacred groves of the Celts, from Norse burial mounds to Greek temples, the land itself is seen as holy. Even in modern cities, pagans find sacredness in parks, rivers, and quiet corners of nature.

Some practitioners seek out ancient sites to reconnect with the energy of their ancestors. Others create sacred spaces at home—an altar, a meditation room, or even a simple shelf with candles and natural objects. The message is the same: the world around us is alive, and every place has spirit.

Modern Pagan Communities

Today, paganism is practiced both individually and collectively. Local covens, groves, and circles meet for rituals, workshops, and celebrations. Large pagan gatherings, such as Pagan Pride Day or seasonal festivals like Beltane Fire in Scotland, attract thousands. Online communities have also flourished, allowing practitioners to connect globally.

These communities offer support, education, and fellowship. They also work to combat stereotypes, showing that pagans are not “devil worshippers” or dangerous outsiders, but people committed to spirituality, ecology, and living in harmony with the Earth.

Misunderstandings and Stereotypes

Despite its growth, paganism still faces many challenges in the modern world. Misunderstandings are common, often fueled by centuries of propaganda. For instance, the Horned God, a fertility figure symbolizing life and nature, has been wrongly conflated with the Christian devil. Similarly, the term “witch” has been stigmatized, though historically it referred to healers, midwives, and wise folk.

Pop culture sometimes worsens these stereotypes. Movies and media often depict witches and pagans as either dangerous or laughable. Yet real pagan practice is deeply spiritual, ethical, and life-affirming. Overcoming these misconceptions requires education, visibility, and continued dialogue with wider society.

The Question of Legitimacy

Because paganism has no central authority or single holy book, critics sometimes question whether it qualifies as a “real religion.” Yet this diversity is one of paganism’s greatest strengths. Like Hinduism or Indigenous traditions, paganism is not bound by dogma but by living relationships—with the Earth, with deities, and with community.

In fact, many governments now officially recognize pagan traditions. Wicca, for example, is a legally protected religion in the United States and the United Kingdom. Pagan chaplains serve in prisons and the military. These developments show that paganism has secured a place in the modern spiritual landscape.

Inclusivity and Diversity

Another strength of modern paganism is its inclusivity. Many traditions emphasize balance between masculine and feminine energies, but they also welcome practitioners of all genders, sexual orientations, and cultural backgrounds. Paganism has become a spiritual refuge for those marginalized by mainstream religions.

This inclusivity makes paganism especially relevant in today’s world. As society becomes more diverse, people seek spiritual paths that reflect their identities and values. Paganism, with its emphasis on freedom and self-expression, thrives in this environment.

The Role of Technology in Pagan Growth

Far from being stuck in the past, paganism has embraced technology. Online forums, social media groups, podcasts, and YouTube channels allow practitioners to share rituals, teachings, and inspiration. Virtual covens meet over video calls. Digital altars and apps track lunar cycles, planetary alignments, and sabbats.

This digital renaissance has allowed paganism to grow beyond geographic and cultural boundaries. A practitioner in rural America can connect with a reconstructionist in Greece or a druid in Ireland. Technology has turned what was once a localized practice into a global community.

Paganism as Resistance and Renewal

In many ways, the modern pagan revival is an act of resistance. It resists consumerism by emphasizing seasonal cycles and handmade ritual tools. It resists patriarchy by honoring goddesses alongside gods. It resists environmental destruction by treating the Earth as sacred.

At the same time, it offers renewal. Paganism renews our relationship with nature, our sense of wonder, and our ability to find meaning in myth and ritual. It reminds us that spirituality need not be confined to institutions—it can be woven into every walk in the forest, every meal shared in gratitude, every night spent gazing at the stars.

Why Paganism Endures

Paganism thrives today for the same reasons it did thousands of years ago: it speaks to something deeply human. It acknowledges our dependence on the Earth, our need for community, our yearning for mystery, and our desire for freedom.

In an age where many feel disconnected—from nature, from one another, from themselves—paganism offers reconnection. It tells us that the world is alive, that the divine is near, and that our lives are part of a greater cycle.

Far from being a relic of the past, paganism is a living, breathing tradition, one that continues to adapt, evolve, and inspire. Its resilience is a testament to the enduring human spirit—a spirit that seeks meaning not in domination, but in harmony; not in rigid rules, but in flowing cycles; not in separation, but in connection.

As we move forward into an uncertain future, perhaps paganism’s greatest gift is this: the reminder that the sacred is all around us—if only we take the time to see.