Roman Pagan Festivals That Shaped Our Calendar

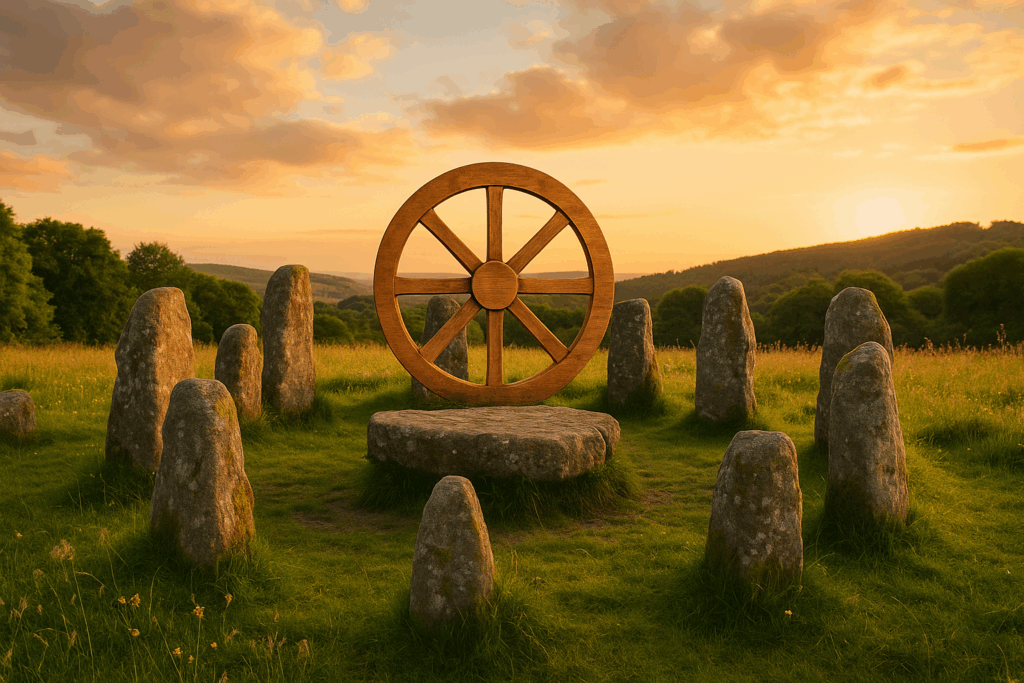

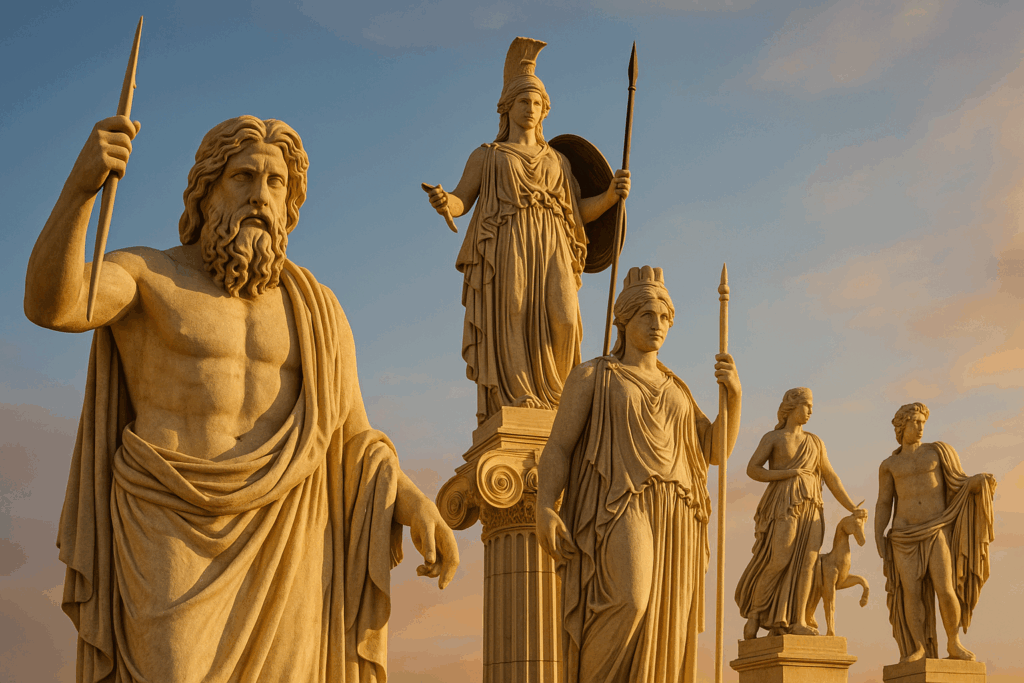

The Roman calendar, though familiar to us today in its modernized form, was born from a world saturated with pagan festivals, rituals, and sacred time. To the Romans, time was not an empty abstraction but a living rhythm shaped by divine cycles. Each month bore the imprint of deities, agricultural labors, and civic obligations, and nearly every week was punctuated by some kind of festival. Far from mere holidays, these observances maintained the cosmic balance, ensuring peace with the gods—the pax deorum—on which the survival of Rome itself depended. What we know as the Western calendar is not simply a neutral measure of days but a descendant of this Roman matrix of sacred time, carrying forward echoes of pagan festivals into modern life. When we celebrate the turning of the year, the months named after gods and emperors, or the feasts that became Christianized, we are living in the shadow of Rome’s sacred calendar.

Among the most formative of Roman festivals was Saturnalia, held in December in honor of Saturn, the god of sowing and agriculture. This festival turned the world upside down: masters served their slaves, gambling was permitted, and revelry overtook restraint. Gifts were exchanged, candles burned, and joy filled the streets in a carnival of inversion and release. The echoes of Saturnalia resonate in our modern Christmas and New Year celebrations, where gift-giving, feasting, and the suspension of normal order create moments of communal joy. Similarly, the Kalends of January, dedicated to Janus, god of doorways and beginnings, directly influenced our New Year traditions. Janus, depicted with two faces, looked backward and forward, embodying the threshold between years. Our resolutions, our marking of transition, all bear his imprint, even if his name has faded from popular memory.

Other festivals marked the year’s agricultural pulse. The Lupercalia in February, dedicated to fertility and purification, saw priests of the Luperci running through the city, striking bystanders with strips of goat hide to ensure fertility and luck. Though often remembered scandalously, this rite reflected Rome’s deep concern with agricultural renewal and human continuation. Its energies echo faintly in Valentine’s Day, another February observance transformed yet retaining its themes of love and fertility. In spring, the Floralia celebrated Flora, goddess of blossoms, with games, theatrical performances, and the wearing of bright garments. This festival of renewal and flowering resonates with our own springtime celebrations, from May Day to Easter, which still carry themes of rebirth, blossoming, and joyous release.

The Roman calendar was also structured by feriae—days sacred to particular gods, when work was suspended, courts were closed, and the divine took precedence. These sacred interruptions wove into the civic year a constant reminder that human life was never separate from divine presence. The Parilia in April honored Pales, protector of shepherds, marking the founding day of Rome itself. The Consualia and Opiconsivia celebrated the gods of stored grain, ensuring abundance for the people. Each of these festivals bound the city’s survival to proper ritual, transforming agriculture and governance alike into acts of devotion. By embedding divine festivals into the very structure of time, Rome made religion inseparable from daily existence.

Though centuries have passed and Christianity reshaped the calendar, Rome’s pagan roots endure in subtle yet profound ways. The months still carry pagan names: March for Mars, May for Maia, June for Juno. The seven-day week owes its planetary gods: Sunday for Sol, Monday for Luna, Saturday for Saturn. Even our leap year system, refined by Julius Caesar in the Julian calendar, reflects a Roman concern with aligning human time to cosmic order. Thus, every glance at a modern calendar is a glance into Rome’s sacred past, where festivals structured the year and human lives were interwoven with the rhythms of divine cycles.

The legacy of Rome’s pagan festivals is best understood through the ways they evolved, transformed, and often survived by blending into later religious and cultural practices. Saturnalia remains one of the clearest examples of this endurance. Held in mid-December, it was originally a one-day feast but expanded over time into a week-long celebration. At its heart was the honoring of Saturn, an ancient agricultural deity whose reign was remembered as a mythical Golden Age of peace and abundance. During Saturnalia, normal hierarchies dissolved—slaves dined with masters, social rules were suspended, and games of chance filled the streets. The atmosphere was one of joyous chaos, a collective catharsis that allowed Roman society to reset itself before winter deepened. When Christianity rose to dominance, it did not abolish Saturnalia outright but absorbed many of its elements into the celebration of Christmas. The gift-giving, candles, greenery, and festive inversion of gloom into joy that mark December holidays are direct echoes of Saturnalia, revealing how Rome’s sacred rhythms still shape our winter festivals.

The Lupercalia, though more obscure, has an equally fascinating afterlife. Celebrated on February 15th, it honored Lupercus, a pastoral deity linked with wolves and fertility. Priests known as Luperci, clad in goat skins, would run through the streets, striking women with strips of hide to grant fertility and ease in childbirth. The festival combined themes of purification, protection, and erotic vitality, its primal energy reminding participants of humanity’s deep bond with animal life and natural cycles. While its direct observance faded, the energies of Lupercalia migrated into later traditions. The Christian feast of Saint Valentine was set in mid-February, gradually absorbing the associations of love and fertility. What survives today as Valentine’s Day—with its themes of desire, union, and courtship—carries a shadow of Lupercalia’s wild joy, domesticated into cards and roses but still fueled by the ancient recognition that love is a sacred, chaotic force woven into the renewal of life.

The Floralia, celebrated in late April and early May, honored Flora, goddess of flowers and blossoms. This festival burst with color, games, and theatrical performances, celebrating the fertility of the earth as spring moved into its full bloom. Revelers donned bright clothing, adorned themselves with flowers, and indulged in spectacles that emphasized renewal and joy. In many ways, Floralia is the ancestor of May Day celebrations, which still crown queens of flowers, raise maypoles, and honor the blossoming of the land. Its influence also survives in Easter customs, where eggs, rabbits, and flowers symbolize fertility and resurrection, blending Christian theology with older seasonal rites. Floralia demonstrates how Roman paganism sacralized not just survival but beauty, recognizing the flowering of fields and gardens as a divine blessing to be celebrated in community.

Equally significant were the Parentalia and Feralia, February festivals dedicated to the dead. During these days, families visited tombs, offering wine-soaked bread, flowers, and prayers to ancestors. The boundaries between living and dead grew porous, allowing communion between generations. These rites remind us that the Roman year was not only shaped by agricultural and civic rhythms but also by the veneration of ancestors. Christianity would later absorb and adapt these customs into All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days, and their legacy still breathes in modern practices of honoring the dead. Festivals like Samhain in Celtic lands or Día de los Muertos in Mesoamerica may differ culturally, yet they share the recognition that seasonal thresholds are times to honor the departed. Rome’s Parentalia ensured that memory and devotion to ancestors were woven into the civic calendar itself.

The Roman calendar was thus more than a list of dates—it was a sacred map, guiding citizens through the cycles of sowing, harvest, rest, remembrance, and joy. Each festival connected Rome not only to its gods but to the eternal forces of fertility, death, and renewal. Christianity may have altered the surface of this map, but its underlying structure persists. Every December feast, every spring celebration of blossoms, every new year’s toast to beginnings and thresholds—each carries the resonance of Rome’s sacred time, where the divine was woven inseparably into civic and agricultural life.

When we step back and view the Roman year as a whole, what emerges is a sacred architecture of time. The calendar did not simply divide days into months and weeks but placed human life within the rhythm of cosmic and divine order. From January’s veneration of Janus at the year’s threshold to December’s Saturnalia at its darkened close, the Romans lived in a world where every season, every cycle of labor, and every shift in nature was acknowledged through festival. This architecture has never been fully dismantled. Christianity overlaid it with saints’ days, feast days, and the liturgical calendar, but the skeleton remains unmistakably Roman. The Christian Easter still orbits the full moon of spring in ways that echo Rome’s seasonal rites; Christmas occupies Saturnalia’s place; Lent and Carnival inherit elements of Roman purifications and feasts of reversal. Even our sense of civic holidays, when the state itself sanctions sacred pauses, reflects Rome’s fusion of governance and ritual.

Central to this structuring of time was the Roman principle of pax deorum—peace with the gods. Every festival, whether exuberant like the Floralia or solemn like the Feralia, existed to maintain right relationship between humans and the divine. The Romans believed their empire thrived not by chance but by dutifully keeping covenant with the gods through sacrifice, festival, and ritual precision. If neglect or error occurred, imbalance could bring famine, disease, or defeat in war. This sense of cosmic reciprocity meant that the calendar was never arbitrary: it was a living cycle of obligations, each festival both thanksgiving and renewal of divine favor. It is telling that even after the fall of paganism as a dominant religion, Christianity retained this same structure of sacred obligation embedded in time. Saints replaced gods, Masses replaced sacrifices, but the rhythm of feast and fast, of solemn remembrance and joyful carnival, remained Roman at its core.

In modern life, many of these echoes persist even when their origins are forgotten. Our New Year, marked with resolutions and thresholds, is Janus’s legacy. Our spring celebrations, whether Easter, May Day, or secular flower festivals, repeat the themes of Floralia. Our winter holidays of light, gift-giving, and reversal of gloom carry Saturnalia’s soul. Even our honoring of the dead in autumn or winter resonates with Rome’s Parentalia, showing that the idea of sacred communion with ancestors is too deeply ingrained to vanish. The modern calendar may appear secular, but beneath it lies the pagan conviction that time is not empty—that it carries meaning, power, and the imprint of divine cycles.

For modern pagans, reclaiming Roman festivals is both an act of heritage and renewal. Groups dedicated to reconstructing Roman religion, sometimes called Religio Romana, observe Saturnalia with feasts and games, pour libations to Janus at the New Year, and honor Vesta at the midsummer Vestalia. Others adapt these observances in personal ways, lighting candles to Saturn in December or leaving offerings to ancestors in February. What matters is less the exact replication of ancient ritual and more the recognition that time itself can be sanctified. By aligning festivals with the turning of seasons and the cycles of nature, modern practitioners reconnect with the rhythm that shaped Rome and, through Rome, much of Western civilization. In doing so, they affirm that calendars are not merely tools for scheduling but sacred texts, recording humanity’s covenant with the cosmos.

Thus the Roman pagan festivals that once ordered the empire’s life still shape our own. They remind us that celebration, remembrance, and renewal are not luxuries but necessities of human existence. They teach that time must be more than mechanical—it must be lived as sacred. And they whisper across centuries that though empires fall and religions change, the gods and rhythms of Rome continue to live in the ways we mark our days, our seasons, and our years.