Exploring the Wheel of the Year: A Beginner’s Guide

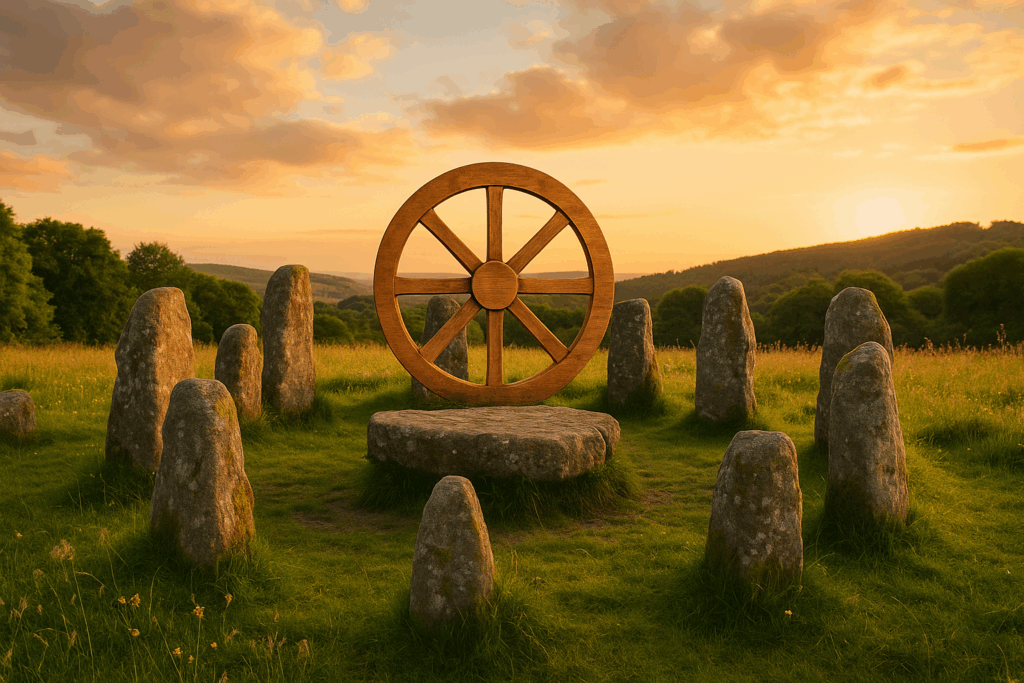

The Wheel of the Year is one of the most enduring and unifying frameworks within modern paganism, a cyclical celebration of the seasons that draws upon ancient agricultural rites, mythological cycles, and deep reverence for the natural world. At its heart, the Wheel represents the eternal turning of time, the dance between light and dark, and the rhythms of growth, harvest, death, and rebirth. To walk in step with this Wheel is to live attuned to the earth’s pulse, honoring the same cycles that sustained our ancestors.

While the term “Wheel of the Year” itself is a relatively modern phrase, the festivals that compose it are rooted in ancient traditions found across Europe and beyond. These seasonal festivals, known to many pagans as Sabbats, weave together myth, ritual, and agricultural life into a sacred calendar. For the beginner, exploring the Wheel can seem both inviting and overwhelming: eight holy days, each with its own lore, symbolism, and practices. Yet to journey through the Wheel is to embark on a spiritual pilgrimage—one that deepens the connection to the land, the gods, and the cycles of one’s own soul.

This extended guide offers not just an overview of each Sabbat but also an exploration of their deeper meaning: their cultural roots, their mythological resonance, and the ways modern pagans integrate them into contemporary practice.

The Origins of the Wheel

The Wheel of the Year as it is commonly known today was developed in the mid-20th century, largely influenced by Gerald Gardner and Ross Nichols, two of the foundational figures of modern Wicca and Druidry. Gardner emphasized the solstices and equinoxes, while Nichols emphasized the “cross-quarter days” (festivals lying between them). Together, these eight festivals became the now-familiar Wheel.

Yet, the roots of these holy days stretch back far into antiquity. The Celts observed fire festivals such as Samhain and Beltane, marking crucial turning points in the agricultural year. The Romans celebrated solstices with grandeur, while Norse and Germanic peoples honored Yule and Midsummer with feasting and sacrifice. Across cultures, humans have long recognized the need to ritualize the passing of seasons, for in the natural cycle lay survival, continuity, and meaning.

In pagan thought, time is not linear but cyclical. Just as the sun rises and sets, the moon waxes and wanes, so too does life proceed in cycles of birth, growth, decline, and death—each leading into renewal. The Wheel of the Year embodies this worldview, a sacred map of time that keeps the practitioner oriented within the great spiral of existence.

The Eight Sabbats of the Wheel of the Year

Yule (Winter Solstice)

Yule, celebrated at the winter solstice, marks the rebirth of the sun. It is the longest night of the year, yet within its darkness lies the promise of returning light. Ancient European traditions centered on fire, evergreen boughs, and feasting—symbols of hope and renewal. The Norse celebrated with twelve nights of Yule, during which the Wild Hunt was believed to ride the winter skies.

For modern pagans, Yule is a festival of rebirth, a time to light candles, burn the Yule log, and honor the Child of Promise, the sun born anew. The evergreen, representing eternal life, finds its echo in the modern Christmas tree.

Imbolc (Early February)

Imbolc, sometimes called Brigid’s Day, celebrates the first stirrings of spring. Though the land still lies in winter’s grip, lambs are born and snowdrops push through the frost. The goddess Brigid, patroness of hearth, poetry, and smithcraft, is honored at this time.

Imbolc is a festival of purification and renewal. Fires and candles are lit to call back the sun. In Celtic tradition, this was also a time to bless seeds and livestock. Modern practitioners often honor Brigid with offerings of milk, weaving Brigid’s crosses, and lighting devotional flames.

Ostara (Spring Equinox)

At Ostara, light and dark stand in balance. Named after the Germanic goddess Eostre, whose symbols were hares and eggs, Ostara is a celebration of fertility and renewal. The earth awakens, buds form on trees, and the promise of growth fills the air.

The equinox speaks of harmony: night and day equal, forces of light and shadow in perfect poise. Eggs and hares remain enduring symbols, found in later Christian Easter traditions. For pagans, this is a time of sowing intentions, planting both literal and metaphorical seeds for the year to come.

Beltane (May 1)

Beltane, opposite Samhain on the Wheel, is a festival of life, passion, and fertility. Fires are lit to bless cattle, fields, and communities. In Celtic lands, couples would leap over flames for luck, while villagers danced around maypoles, weaving the ribbons into patterns of union.

This is a festival of love and vitality, of sacred sexuality and the union of opposites. Modern pagans may celebrate with bonfires, floral garlands, and handfasting rituals. The May Queen and Green Man, archetypes of life force and fertility, are honored.

Litha (Summer Solstice)

At Litha, the sun stands at its zenith. The day is longest, the night shortest. Yet even in this moment of fullness lies the seed of decline, for from here the light begins to wane.

Midsummer was widely celebrated across Europe with fires, feasts, and revelry. Herbs gathered at this time were believed to hold great potency. Modern pagans honor the strength of the sun, celebrate abundance, and gather outdoors for ritual. The Oak King and Holly King myth—where the Oak King rules the waxing year and the Holly King the waning year—is often dramatized at Litha.

Lughnasadh / Lammas (August 1)

Lughnasadh, or Lammas, is the first harvest festival. It is named for the god Lugh, a warrior and craftsman of Celtic lore. Traditionally, communities baked the first loaves of bread from newly harvested grain, offering them in thanks.

This is a time of gratitude, sacrifice, and community sharing. The cutting of the first sheaf symbolizes both death and sustenance: the grain must die for people to live. Modern rituals often involve baking bread, feasting, and reflecting on the fruits of one’s labor.

Mabon (Autumn Equinox)

Like Ostara, Mabon is a time of balance, when light and dark stand equal. Yet here the emphasis is on gratitude and preparation, as the year wanes toward winter. The harvest is gathered, and communities give thanks for abundance.

Named in modern times after a Welsh deity, Mabon is not an ancient Celtic holiday but has found resonance among pagans as a festival of thanksgiving. Rituals often involve sharing meals, honoring the earth’s bounty, and contemplating balance within one’s life.

Samhain (October 31 – November 1)

Samhain is the most solemn and mysterious of the Sabbats. It marks the Celtic New Year, the time when the veil between worlds is thinnest. Ancestors are honored, and the dead are invited to feast at the table.

Bonfires once blazed across Celtic hillsides, cattle were driven between them for blessing, and divination was practiced widely. Today, Samhain remains a time for ancestor veneration, for reflection on mortality, and for seeking wisdom from the unseen. Halloween, with its costumes and jack-o’-lanterns, is a cultural echo of this ancient festival.

Walking the Wheel: Symbolism and Spiritual Lessons

The Wheel of the Year is more than a calendar; it is a map of the soul’s journey. Each festival offers lessons not only about the natural world but also about the cycles of human life. Yule’s rebirth speaks to our own ability to find light in the darkest times. Beltane’s passion reminds us of creativity and connection. Samhain’s solemnity calls us to honor endings and embrace transformation.

To live with the Wheel is to accept the ebb and flow of existence. Just as no season lasts forever, so too joy and sorrow, growth and rest, all pass in their time. For many pagans, aligning one’s practice with the Wheel fosters mindfulness, resilience, and reverence for the sacred dance of life.

For the beginner, exploring the Wheel of the Year is an invitation into a deeper relationship with the earth and with the cycles that shape both nature and human existence. Each turn of the Wheel brings opportunities for reflection, celebration, and transformation. Though modern paganism has adapted and reimagined these festivals, their roots in seasonal rhythms remain timeless.

To honor the Wheel is to walk in step with ancestors who looked to the sun and stars, who lit fires against the dark, who feasted in gratitude, and who mourned and rejoiced as the seasons turned. Today, in a world often disconnected from natural cycles, the Wheel offers not just tradition but a profound spiritual compass.