Divination in Pagan Traditions: Runes, Tarot, and More

From the dawn of time, humans have sought to pierce the veil of uncertainty, to glimpse patterns hidden beneath the flux of life, and to draw meaning from signs both subtle and profound. Divination, in its many forms, has always been more than prediction—it is dialogue with the unseen, a way of attuning human consciousness to the voices of gods, ancestors, and spirits that shape existence. For pagans, divination was never merely a curiosity but an essential aspect of spiritual practice, a tool for decision-making, guidance, and communion with the sacred. To cast runes, draw cards, read omens in flight of birds or patterns in fire, is to step into a liminal space where the ordinary and extraordinary converge. Divination is ritualized listening, the art of perceiving what is already written in the fabric of the cosmos.

In the ancient world, divination took countless forms, each culture shaping its practices according to cosmology and local traditions. The Greeks consulted the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, where priestesses inhaled vapors and uttered words believed to carry divine truth. Romans observed the flights of birds, the entrails of sacrificed animals, or the cracks in lightning, convinced that the gods communicated through every natural phenomenon. The Celts used omens, dreams, and perhaps even early forms of casting lots, guided by druids who were trained interpreters of the hidden. In each case, the diviner did not “create” knowledge but uncovered patterns already woven into existence, revealing the sacred order to those who asked.

Among the Norse, runes became one of the most enduring forms of divination. According to myth, Odin himself hung upon the World Tree, Yggdrasil, wounded and fasting, until he glimpsed the runes—symbols of cosmic power—and seized them as gifts for gods and men. To carve or cast runes was to participate in this divine mystery, to summon forth guidance through the sacred alphabet. Each rune carried layers of meaning—fehu for wealth, uruz for strength, ansuz for divine breath—and when cast, they formed messages that spoke to both immediate concerns and deeper spiritual truths. Unlike fortune-telling, rune-casting was less about prediction than about uncovering currents at work, revealing the energies shaping a situation and how one might align with or resist them. In this way, the runes functioned not only as script but as living forces, each symbol a doorway to myth and mystery.

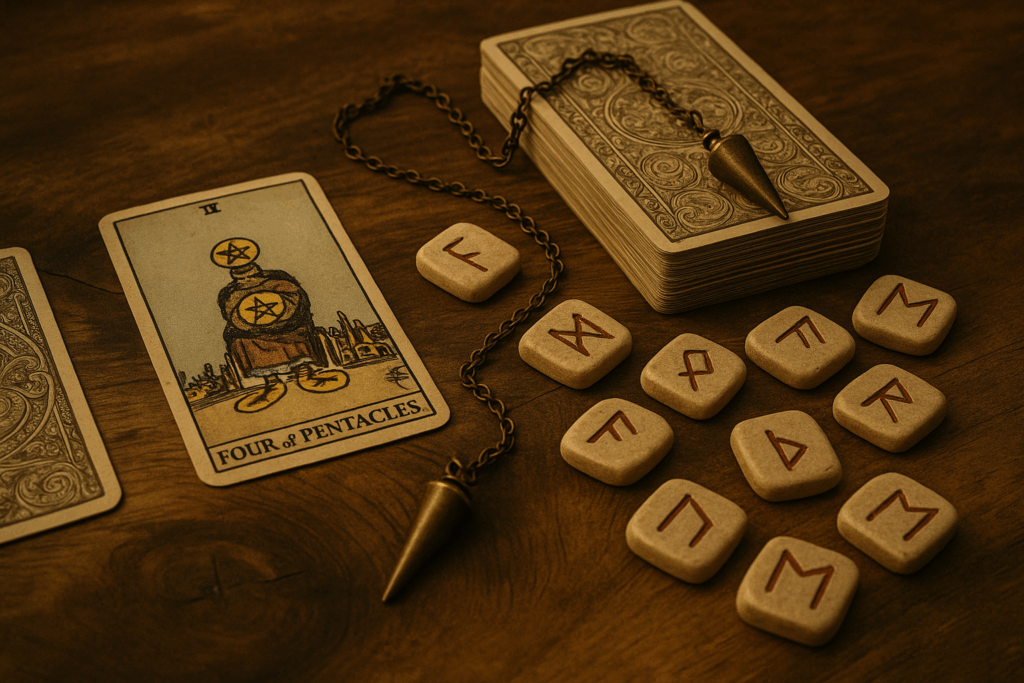

Tarot, though emerging later in history from Renaissance Europe, has become one of the most recognizable tools of divination in modern pagan practice. Its seventy-eight cards form a symbolic universe, weaving archetypes, numbers, and images into a system of spiritual exploration. The Major Arcana—cards such as The Fool, The Magician, and Death—represent archetypal stages of the soul’s journey, while the Minor Arcana detail the nuances of daily life, each suit carrying elemental resonance. To draw cards is to open a mirror into the subconscious and into the greater web of fate, where intuition and symbolism converge. For pagans, Tarot is more than prediction; it is meditation, storytelling, and sacred dialogue, allowing the practitioner to engage with the spiritual currents that shape both inner and outer worlds.

Pendulums, crystal balls, scrying bowls, and countless other methods have joined runes and Tarot in the pagan repertoire. Each technique reflects the same core principle: that reality is not closed but permeable, and that through ritual focus, one can perceive beyond the surface. The pendulum swings in answer to questions, guided not by chance but by subtle energies. Water in a dark bowl reveals images to the attuned eye. Flames or smoke carry patterns for the patient observer. Dreams, too, are honored as oracles, messages from ancestors or spirits cloaked in symbolic form. All these methods are united by a conviction that the cosmos speaks, and that humans can learn to listen.

In its essence, divination is less about control than about communion. It does not guarantee certainty but invites humility, teaching that the world is alive with signs, and that wisdom lies in reading them well. For pagans ancient and modern, divination is the art of attunement: aligning oneself to the voice of the gods, the flow of fate, and the whispers of the unseen.

Divination in pagan cultures was always rooted in their cosmology: how a people understood the structure of the universe, the will of the gods, and humanity’s place within it. Among the Celts, divination was bound up with the role of the druid, the intermediary between human and divine. Accounts from Roman writers, though often colored by bias, suggest that druids practiced various forms of omen-reading and augury. Birds in flight, the rustling of oak leaves, or the patterns of flames might be interpreted as messages from the Otherworld. Water held particular significance: seers gazed into wells, lakes, or cauldrons to perceive visions, for these were portals into realms beyond the visible. The myths of the Celtic hero Finn MacCool illustrate this principle vividly—by tasting the Salmon of Knowledge, he gained the gift of wisdom, a story symbolizing the druidic art of discerning truth hidden within nature’s symbols. For the Celts, divination was not abstract fortune-telling but direct engagement with the spirit-infused landscape.

In Greece and Rome, divination was woven into civic as well as personal life, forming a vital part of governance, warfare, and agriculture. No major decision in Rome was undertaken without consultation of the augurs, priests who interpreted the will of the gods through the flight of birds and other natural phenomena. Haruspices, another class of diviners, examined the entrails of sacrificial animals, believing that the gods inscribed their messages into the organs of life. The Greeks consulted oracles such as the famous Pythia at Delphi, whose pronouncements, though often cryptic, guided city-states in war, colonization, and law. Even common citizens practiced forms of divination: casting lots, interpreting dreams, or seeking omens in daily life. This institutional integration of divination demonstrates that for Mediterranean paganism, discerning the gods’ will was not optional—it was the very foundation of communal order. Without it, the pax deorum, the peace with the gods, could not be maintained.

Norse divination, while less centralized, carried equal weight in shaping life and fate. The sagas speak of völur, prophetesses who traveled between communities offering visions and counsel. These women, often elderly and highly respected, practiced seiðr, a form of magic and divination that involved trance, chanting, and spirit journeying. Their prophecies might concern the outcomes of battles, the fates of rulers, or the health of a community. Their authority derived not only from their skill but from their role as vessels of divine insight. Alongside these professional seers, ordinary people employed runes as tools for daily guidance. The runes were not only letters but sacred signs, each resonating with mythic power. To carve a rune into wood, bone, or stone was to invoke its force directly, while to cast them in lots was to invite the gods’ counsel. Norse divination thus blended formal ritual, ecstatic vision, and everyday practice, embedding prophecy deeply into community life.

Outside Europe, we see striking parallels in the ways divination functioned as dialogue with the unseen. In West African traditions, the Yoruba practice of Ifá involves an intricate system of divinatory verses and symbolic patterns cast with palm nuts or cowrie shells. Each pattern opens a gateway into mythic wisdom, guiding the seeker with stories of Orishas and cosmic principles. In China, the I Ching has served for millennia as a manual of divination, interpreting the changing lines of hexagrams as mirrors of cosmic movement. Like runes or Tarot, the I Ching reveals underlying currents rather than fixed futures, teaching that destiny is dynamic and relational. These parallels remind us that divination is a nearly universal human practice, reflecting the conviction that the world is not mute but saturated with meaning.

What binds all these traditions together is the belief that divination reveals patterns rather than dictates them. The gods or spirits may guide, but they do not always command. The augur’s birds, the druid’s leaves, the völva’s vision, or the Tarot’s spread all reveal possibilities, tendencies, and pathways, leaving room for human agency. Divination thus fosters responsibility as much as revelation—it calls the seeker to discern, to choose wisely, and to act in harmony with the greater forces at play. For pagans, to practice divination is to acknowledge that life is a dialogue with destiny, one in which human choice and divine will dance together in perpetual rhythm.

At the heart of every form of divination lies the recognition that the universe speaks in symbols. These symbols may appear as runes carved into bone, cards painted with archetypes, lines formed by shells, or patterns glimpsed in fire and water. To practice divination is to learn the grammar of these symbols, to train the mind and spirit to perceive resonance where the untrained eye sees only randomness. This symbolic worldview is fundamentally pagan: it asserts that the world is alive, that spirit permeates all matter, and that meaning is woven into every phenomenon. Nothing is empty. Every event, every sign, every coincidence may serve as a thread connecting the mortal and divine.

The Norse runes embody this principle with striking clarity. Each rune is more than a letter; it is a force, an archetype, a distillation of cosmic power. Fehu signifies wealth, but also the primal energy of cattle, abundance, and exchange. Uruz means wild strength, the aurochs, the raw vitality of life. Ansuz is the breath of Odin, the gift of speech and inspiration. To cast runes is not to spell words but to weave patterns of meaning, to see how these forces are active in a given moment. The runes remind us that language itself is sacred, that to inscribe or utter symbols is to participate in creation. Their use as divinatory tools highlights the pagan conviction that destiny and story are bound by the same threads of mythic pattern.

Tarot, though a later system, carries similar symbolic depth. Each card is a mirror of archetypal forces—the Magician as will and manifestation, the High Priestess as intuition and hidden knowledge, the Tower as sudden destruction and revelation. Together, the cards map the journey of the soul through cycles of growth, death, and renewal. When a spread is laid out, it is not the future in mechanistic detail that is revealed, but a story—a narrative thread that helps the seeker understand their place within a greater pattern. Tarot thus functions as both divination and spiritual psychology, drawing the querent into dialogue with the archetypes that shape their life. In modern pagan practice, Tarot has become one of the most widespread and versatile tools, bridging the ancient art of omen-reading with contemporary quests for self-knowledge.

Beyond specific tools, the philosophy of divination rests on the belief that signs and synchronicities are threads of connection between worlds. To read an omen in the flight of birds or the pattern of smoke is not to impose meaning but to recognize meaning already present. This requires a cultivated sensitivity, a willingness to step out of the ordinary mindset and into a state of receptivity. Diviners often prepare with ritual—purifying themselves, invoking gods or spirits, entering trance—to attune their consciousness. This process underscores the truth that divination is not about control or domination but about humility. It is the practice of listening to forces greater than oneself, acknowledging that human perception is limited but can be expanded when aligned with sacred presence.

In modern paganism, divination has taken on new dimensions, serving not only as ritual practice but as a way of weaving the sacred into daily life. Many practitioners pull a rune or Tarot card each morning, not to fix the day’s events but to open themselves to reflection and alignment. Others consult the cards or runes during turning points—before a move, a relationship decision, or a spiritual undertaking—using divination as counsel rather than command. Dreams are kept in journals, synchronicities noted, omens honored as the voice of the gods breaking through the noise of daily existence. In this way, divination becomes less a rare oracular act and more a continuous dialogue with the world, affirming the pagan conviction that life itself is a ritual, and every moment can speak if we are willing to hear.

Thus, divination in pagan traditions is far more than fortune-telling. It is a philosophy, a way of being in the world that recognizes symbol, spirit, and pattern as the true fabric of reality. Whether through the ancient staves of Odin, the painted archetypes of Tarot, or the countless omens of nature, divination offers a way to live more deeply attuned, more reverent, and more responsive to the currents of fate and freedom alike.