Celtic Paganism: Key Beliefs and Traditions

The World of the Celts

The Celts were not a single people bound by one homeland but rather a constellation of tribes spread across much of Europe, from the British Isles to Gaul, Iberia, and even into Anatolia. Their culture was not fixed but fluid, shaped by migrations, wars, and exchanges with neighboring civilizations. Yet across these vast territories, certain threads of belief, ritual, and worldview endured, forming what we now understand as Celtic paganism. This was a spirituality deeply entwined with the land, its cycles, and its mysteries, one that blended mythology, ritual, and lived experience into a seamless whole. To speak of Celtic paganism is to enter a world where gods walked in groves, where rivers held spirits, where kings ruled not merely by force but by sacred contract with the land itself.

The Sacredness of Nature

At the heart of Celtic spirituality was an intimate reverence for the natural world. Forests, rivers, mountains, and stones were not inert matter but living presences imbued with divine force. The Celts saw the landscape itself as a sacred text, its features alive with the footprints of gods and ancestors. Sacred groves were centers of ritual, places where the veil between worlds was thin and where druids offered sacrifices and divinations. Rivers were personified as goddesses, such as Boann, the spirit of the River Boyne in Ireland, whose waters symbolized fertility and poetic inspiration. Stones and hills, too, bore divine associations, often serving as landmarks for gatherings or boundaries for ritual territories. This sacralization of landscape ensured that daily life was never divorced from spirituality; to walk the land was to traverse the body of the divine.

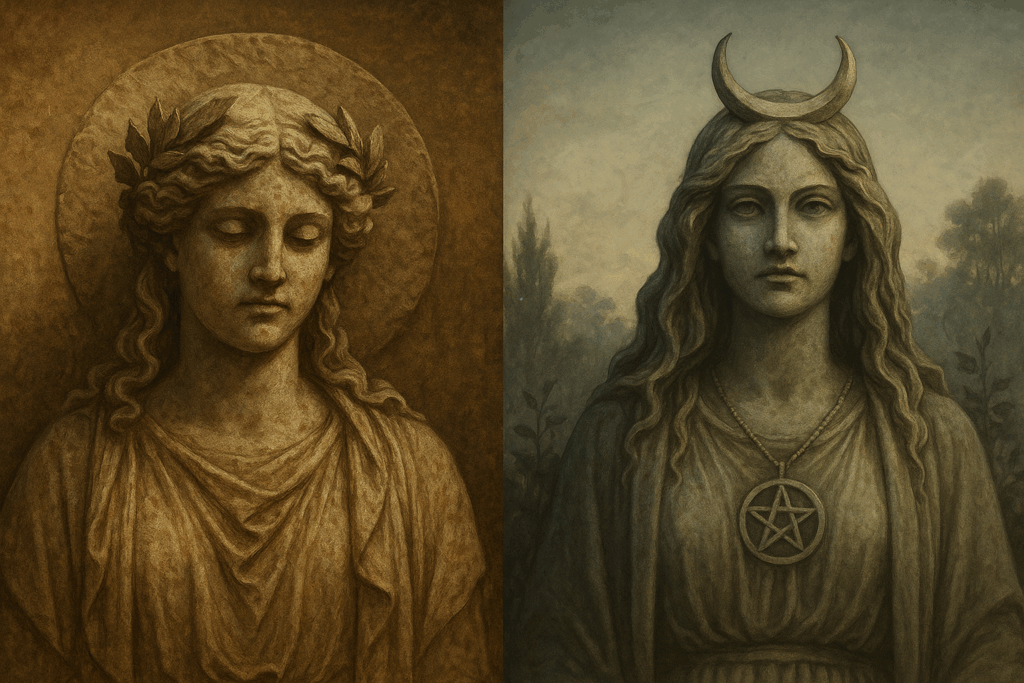

The Celtic Pantheon

Though fragmented in sources, the Celtic pantheon emerges as a tapestry of gods and goddesses, each reflecting essential aspects of life, death, and the natural world. The Dagda, known as the “Good God,” embodied abundance, wisdom, and sovereignty, wielding a cauldron that never emptied. Brigid, goddess of poetry, healing, and smithcraft, became one of the most beloved figures, her influence enduring even into Christian times as Saint Brigid. Lugh, master of all arts, represented the divine power of versatility, celebrated at Lughnasadh, the festival of the first harvest. Morrigan, the complex goddess of battle, fate, and sovereignty, revealed the darker and transformative aspects of divinity, appearing as a crow on battlefields. These deities were not abstract but deeply connected to the cycles of nature and human life, their myths echoing the realities of war, fertility, artistry, and death that the Celts experienced.

Druids and Sacred Knowledge

Perhaps the most enduring symbol of Celtic paganism is the druid: the priest, poet, judge, and keeper of sacred lore. Druids were not only ritual leaders but guardians of wisdom, transmitting their knowledge orally through generations. They studied astronomy, law, medicine, and poetry, integrating these disciplines into a unified worldview that saw no separation between science and spirituality. Druids presided over sacrifices, conducted divination, and advised kings, ensuring that human society remained aligned with the divine order. Their reverence for the oak tree, whose name may even lie behind the word “druid,” symbolized their role as mediators between heaven and earth, as oaks themselves were seen as pillars uniting the worlds above and below. To understand Celtic paganism without acknowledging the druids would be impossible, for they were the interpreters of its mysteries, the keepers of its mythic and ritual coherence.

Cyclical Time and the Festivals

Celtic paganism was deeply oriented around cyclical time, where the year was marked by seasonal festivals that wove together agriculture, cosmology, and myth. Samhain, the feast of the dead at the threshold of winter, honored ancestors and marked the thinning of the veil. Imbolc, dedicated to Brigid, celebrated the returning light and the stirrings of spring. Beltane, a fire festival, consecrated fertility and union, ensuring the abundance of summer. Lughnasadh, tied to Lugh, marked the first harvest and honored both agricultural labor and human skill. These festivals did not merely commemorate seasonal changes but were moments when human life was ritually synchronized with cosmic order. Through fire, feasting, and offering, the Celts enacted their role within the cycles of nature, ensuring harmony between community, land, and the divine.

Death and the Afterlife in Celtic Thought

For the Celts, death was not an ending but a transition, a movement between realms in an eternal cycle of existence. Classical writers, including Julius Caesar, remarked on the Celtic belief in the immortality of the soul, suggesting that this conviction gave their warriors fearlessness in battle. Archaeological evidence, such as lavish grave goods buried with chieftains and warriors, confirms that the Celts saw the afterlife as a continuation of earthly life. Swords, cauldrons, jewelry, and even chariots were laid in tombs, preparing the deceased for a vibrant existence beyond the grave. Mythology reinforces this worldview through tales of the Otherworld: a realm of abundance, beauty, and timelessness. The Irish stories of Tir na nÓg, “the Land of Youth,” speak of a place where death holds no sway and joy endures without decay. The Welsh Annwn carries similar associations of mystery and plenty. To die, then, was not to vanish but to enter another phase of the soul’s journey, a belief that infused Celtic paganism with profound resilience and reverence for the cycles of life.

Sovereignty and the Land

A central theme in Celtic spirituality was the sacred bond between ruler and land. Kingship was never merely political but sacramental, validated by the blessings of the earth and its divine guardians. Myths often depict goddesses of sovereignty offering the throne to kings through ritual unions, affirming that just rule required harmony with the land itself. When kings failed in their duties, famine, war, or plague might follow, for imbalance between ruler and earth disrupted the sacred order. The goddess Ériu, from whom Ireland takes its name, exemplifies this role, embodying the spirit of the land and demanding proper reverence. This principle of sovereignty illuminates how the Celts perceived authority not as domination but as stewardship bound to spiritual accountability. For modern pagans, this teaching continues to resonate, reminding us that leadership and ecological balance are inseparable, and that to honor the land is to honor the divine.

Sacred Symbols and Art

Celtic art and symbolism are among the most enduring legacies of their spirituality, rich with meaning that extended beyond aesthetic beauty. The intricate spirals, knots, and interlacing patterns found on stones, jewelry, and manuscripts are not mere decoration but expressions of cosmology and eternity. The spiral, for example, represents both the cycle of life and the journey inward toward spiritual insight. The triskele, a triple spiral motif, embodies triplicity—life, death, and rebirth; land, sea, and sky; or maiden, mother, and crone. Knotwork, with its endless lines, symbolizes the interconnectedness of existence and the eternal flow of spirit. Animals, too, held symbolic weight: boars stood for courage, stags for sovereignty, ravens for prophecy, and salmon for wisdom. These symbols were woven into daily life, ensuring that every tool, ornament, and monument carried spiritual resonance. Through art, the Celts expressed the sacred patterns that governed their world, embedding theology into material culture.

Cosmology and the Structure of the World

Celtic cosmology envisioned a universe composed of multiple realms, interwoven and permeable. Land, sea, and sky formed the triadic structure of existence, each realm governed by divine powers yet interconnected in sacred balance. The Otherworld, far from being remote, lay just beyond the veil, accessible through mounds, caves, lakes, or moments of liminality. Time itself was cyclical, with festivals marking thresholds when the boundaries between worlds grew thin and encounters with gods or spirits were possible. This cosmology emphasized permeability rather than separation, affirming that the sacred was always near at hand. The druidic reverence for the oak, which reaches skyward with its branches and delves deep into the earth with its roots, embodies this worldview of interconnected realms. In Celtic paganism, existence was never confined to the material alone but was a constant interplay of visible and invisible forces, human and divine, mortal and eternal.

Ritual Practice and Offerings

Celtic ritual life centered on maintaining harmony with gods, spirits, and ancestors. Offerings of food, drink, weapons, and jewelry were made at rivers, lakes, and bogs, places understood as portals to the Otherworld. Archaeological finds, such as the Gundestrup Cauldron or the rich hoards of weapons deposited in watery sites, reveal the scale and seriousness of these acts. Sacrifice, both animal and human, though controversial in historical accounts, appears to have been part of certain rituals, meant to ensure cosmic balance or secure divine favor. Rituals were often accompanied by fire and feasting, uniting the community in acts of devotion that were as celebratory as they were solemn. The communal dimension of ritual was vital: to honor the gods was not only a personal duty but a collective one, binding tribe and land together in sacred reciprocity. Through these rites, the Celts affirmed their place in the cosmic order, ensuring balance between human effort and divine blessing.

Prophecy and the Role of Divination

Celtic societies did not approach the future as a fixed path but as a tapestry woven from choices, omens, and the will of the gods. Divination was a key component of their religious practice, providing guidance for leaders, warriors, and communities. Druids and seers interpreted the flight of birds, the patterns of flames, or the shapes of clouds, reading in them messages from the Otherworld. Ogham, the ancient script of Ireland, carved into wood or stone, could also serve as a tool for divination, each symbol resonating with the spirit of a tree or natural force. Prophecy was not merely prediction but communication—a dialogue between human beings and the divine order. These practices underscored the belief that nothing in the world was random; every sign carried meaning, and the gods spoke through the language of nature. For modern pagans, reviving such practices can deepen the sense of living in a world alive with symbols, where the sacred reveals itself in subtle and unexpected ways.

Hero Myths and Sacred Storytelling

Celtic mythology teems with heroes whose stories exemplify the values, struggles, and spiritual truths of their culture. Figures like Cú Chulainn, whose ferocity and tragic fate embody both warrior virtue and human vulnerability, were not only entertainment but moral exemplars. Finn MacCool, leader of the Fianna, represents wisdom, courage, and connection to the natural world, particularly through the famous tale of his gaining wisdom by tasting the Salmon of Knowledge. These heroes often interacted with gods, spirits, and the Otherworld, blurring the boundaries between myth and ritual. Storytelling was itself a sacred act, preserving ancestral wisdom and transmitting the cosmological truths that grounded the community. In bardic tradition, the poet held power akin to the druid, weaving words that carried blessing, curse, or prophecy. Hero myths thus functioned as more than narratives; they were living lessons that reinforced the cosmology and ethics of Celtic paganism.

The Survival of Pagan Traditions

With the arrival of Christianity, much of Celtic paganism underwent transformation rather than eradication. Pagan deities were reimagined as saints, sacred sites were rededicated to Christian worship, and festivals were adapted into the liturgical calendar. Brigid is perhaps the most famous example, her cult surviving in the figure of Saint Brigid, whose feast day on Imbolc preserved older themes of fertility, healing, and fire. Samhain endured as All Hallows’ Eve and later Halloween, carrying forward the sense of liminality and contact with the dead. Wells, groves, and stones continued to be venerated under Christian guise, reflecting the persistence of animistic reverence. Folklore preserved many of the old myths and practices, often blending them seamlessly with Christian motifs. In this way, Celtic paganism never truly disappeared but lived on in folk custom, storytelling, and seasonal celebration, awaiting rediscovery by modern seekers.

The Modern Revival

The twentieth and twenty-first centuries have witnessed a remarkable revival of Celtic paganism, with neo-pagan and druidic movements drawing upon historical sources, folklore, and spiritual intuition to reconstruct ancient practices. Groups such as the Order of Bards, Ovates, and Druids have sought to revive druidic wisdom in forms suited to contemporary life, emphasizing ecological awareness, poetic inspiration, and ritual connection with the land. Festivals like Beltane are celebrated anew, often with fire ceremonies, dancing, and offerings to honor the cycles of nature. Modern Celtic paganism is both a reconstruction and a living tradition, combining historical research with creative adaptation to address present needs. It offers a spirituality rooted in place, season, and ancestry, inviting practitioners to step into the same rhythms of reverence that once guided ancient communities.

The Enduring Spirit of Celtic Paganism

Celtic paganism endures not because it has been preserved in pristine form but because it speaks to enduring human needs: to live in harmony with nature, to find meaning in cycles of time, to honor ancestors and deities, to weave artistry into life, and to treat death as a transformation rather than an end. It reminds us that the land is sacred, that sovereignty lies in balance, that symbols carry power, and that myth and ritual are essential to human flourishing. In an age where many feel disconnected from the earth, Celtic traditions offer pathways back into relationship with land, season, and story. To walk in the footsteps of the Celts is to recognize that every stone, river, and flame still speaks, if only we learn to listen.