Ancient Paganism vs. Modern Paganism: What’s Changed?

The Persistence of Pagan Traditions

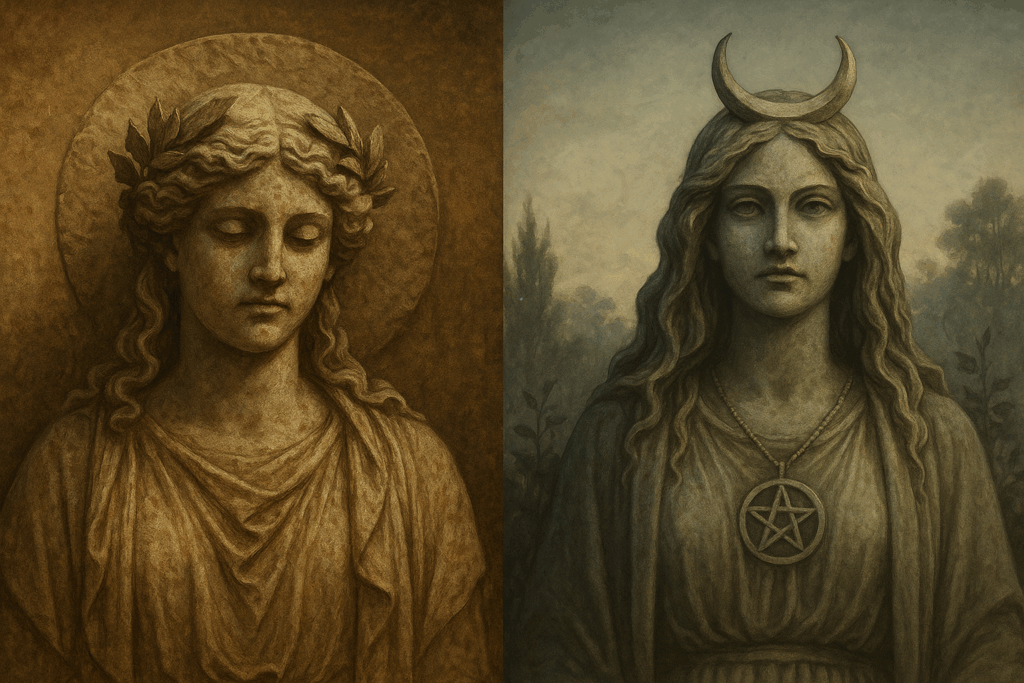

When people hear the word “paganism,” it often conjures images of ancient temples, firelit rituals, and the worship of gods whose names echo faintly from myth: Odin, Isis, Brigid, Pan. For centuries, the word was used as a catch-all by Christian chroniclers to describe the myriad non-Christian religions across Europe, the Mediterranean, and beyond. Ancient paganism was not one faith but a vast tapestry of localized spiritual traditions tied to land, kinship, and the rhythms of survival. Modern paganism, on the other hand, represents a revival, reconstruction, and reimagining of these old pathways, emerging in the twentieth century as both a spiritual movement and a cultural identity. To understand what has changed, one must first appreciate the deep commonalities between past and present: reverence for nature, respect for cycles of time, and the recognition of divine presence in the multiplicity of gods, spirits, and forces animating the world.

The persistence of these values shows that paganism has never truly died, even when suppressed. Instead, it has shifted forms, moving underground during eras of persecution, surviving in folk customs, seasonal festivals, and rural traditions. Today’s modern pagans inherit not only fragments of the ancient world but also the creative freedom to shape them anew, crafting a spirituality that honors both ancestral wisdom and contemporary realities.

Ancient Paganism: A World of Many Gods

Ancient pagan traditions were as diverse as the landscapes they emerged from. The Celts of Iron Age Europe built their religious life around deities of fertility, war, and the sacred landscape, while the Greeks told grand tales of the Olympian gods whose dramas reflected both cosmic order and human folly. The Romans organized their pantheon with a practical eye, adapting foreign gods into their empire while maintaining an elaborate system of civic and household worship. The Norse peoples turned to Odin, Thor, and Freyja for guidance in battle and fertility, while Slavic tribes honored spirits of rivers, forests, and ancestors.

A defining feature of ancient paganism was its integration into every aspect of daily life. Religion was not separate from politics, agriculture, or family but was the fabric through which society held together. Seasonal festivals marked the agricultural year; kings and chieftains were often both rulers and ritual leaders; omens and divination shaped decisions of war and governance. Sacred groves, springs, and mountains were considered alive with spiritual presence, places where offerings were made not out of abstract belief but out of practical reciprocity.

There was also no central scripture. Ancient pagan traditions were oral and local, passed down through ritual, myth, and community practice. Gods and spirits could vary from valley to valley, their stories shifting with each telling. This diversity gave ancient paganism its vitality but also made it vulnerable to disappearance once oral traditions were disrupted.

The Decline and Transformation of Ancient Paganism

The decline of ancient pagan traditions cannot be understood solely as a sudden Christian replacement. It was a gradual process, stretching over centuries, as imperial edicts, missionary campaigns, and cultural assimilation reshaped the religious landscape. Temples were closed, priesthoods dismantled, and sacred groves cut down. Yet elements of pagan life persisted beneath the surface, often absorbed into Christian practice. Saints replaced gods, holy wells remained sites of pilgrimage, and festivals such as Yule, Beltane, and Samhain endured in folkloric guise.

The demonization of pagan deities also contributed to their fading from mainstream memory, with horned gods recast as devils and fertility rites portrayed as dangerous excess. Yet even in these distortions, pagan echoes endured. What changed most dramatically was not the spirit of reverence for nature or ancestors but the social structures that supported them: temples, priesthoods, and state cults gave way to a centralized monotheism.

The Rise of Modern Paganism

Modern paganism, sometimes called Neopaganism, began to take shape in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries amidst a renewed fascination with folklore, mythology, and esoteric traditions. Romantic poets like William Blake and Percy Shelley celebrated the old gods as symbols of imagination and rebellion. Folklorists collected rural customs that preserved echoes of pre-Christian belief. Secret societies and occult movements, such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, drew upon pagan imagery in their rituals.

The true turning point came with the emergence of Wicca in the mid-twentieth century, pioneered by Gerald Gardner. Wicca presented itself as a revival of witchcraft and ancient pagan religion, emphasizing reverence for nature, the cycles of the moon, and the worship of a goddess and god. Around the same time, Ross Nichols revitalized Druidry, reimagining Celtic spirituality for modern seekers. Other reconstructionist movements soon followed: Heathenry sought to revive Norse religion, Hellenism focused on Greek practice, and Slavic pagans restored old rituals of their ancestors.

Modern paganism is not simply a nostalgic reconstruction but a living spirituality adapted to contemporary concerns. It is pluralistic, decentralized, and creative. Practitioners may focus on historical reconstruction, intuitive personal practice, or eclectic blends of traditions. Unlike ancient paganism, it exists within a global, interconnected world, where practitioners across continents can share rituals and insights.

What Has Changed Between Ancient and Modern Paganism?

The differences between ancient and modern paganism are profound, shaped by historical, cultural, and social transformations. Ancient paganism was a community religion embedded in daily life, reinforced by political authority and social obligation. Modern paganism is primarily a matter of personal choice, spiritual identity, and voluntary community. Where ancient festivals ensured agricultural survival, modern ones nurture spiritual growth, ecological awareness, and cultural identity.

Another difference lies in sources of knowledge. Ancient pagans lived within an unbroken chain of oral tradition, myth, and ritual. Modern pagans often rely on archaeology, folklore studies, and scholarly interpretation to reconstruct what was lost. This reliance on scholarship makes modern paganism both flexible and contested, as practitioners debate the authenticity of rituals and symbols.

The relationship with modern society also differs. Ancient paganism was mainstream, the dominant worldview of its time, while modern paganism often exists on the margins, a minority faith. Yet this outsider status grants modern practitioners freedom to define and adapt their paths without state interference.

Perhaps most significantly, modern paganism often emphasizes inclusivity, equality, and ecological consciousness in ways ancient traditions did not. While ancient cults could be hierarchical, exclusive, and tied to social roles, modern paganism tends to welcome diversity of gender, orientation, and background. The ecological crisis of our era has also given pagan spirituality a renewed urgency, with reverence for the earth becoming not only spiritual but ethical.

Shared Threads Across Time

Despite the differences, the threads connecting ancient and modern paganism are undeniable. Both view the world as alive, sacred, and cyclical. Both honor deities, spirits, and ancestors as real presences deserving of respect. Both find meaning in ritual, seasonal festivals, and the turning of nature’s wheel. Modern pagans may not sacrifice at temples or pour libations into sacred springs in the same manner, yet their rituals echo the same human impulse to connect with forces larger than themselves.

In this way, modern paganism can be seen not as a return to the past but as a dialogue with it. Ancient traditions inspire, but the spiritual needs of today shape how they are practiced. The revival of polytheism, the honoring of local spirits, and the celebration of seasonal festivals are acts of continuity across millennia.

The Continuing Evolution of Paganism

Looking at both ancient and modern expressions of paganism reveals a religion not bound by dogma but by relationship: relationship with land, with gods, with ancestors, and with community. In ancient times, these relationships ensured survival; today, they offer healing for souls seeking connection in a fragmented world. Paganism has always been adaptive, absorbing influences and reshaping itself according to circumstance.

The essence of pagan spirituality remains in its adaptability, in its ability to honor diversity, and in its refusal to be confined to a single definition. What has changed is less the heart of paganism than the context in which it is practiced. Ancient pagans and modern pagans alike turn to the rising sun, the growing grain, and the voices of their gods for guidance, celebration, and reverence. In that shared devotion, separated though they may be by centuries, they stand in continuity with one another, participants in a great and unbroken conversation between humanity and the sacred world.