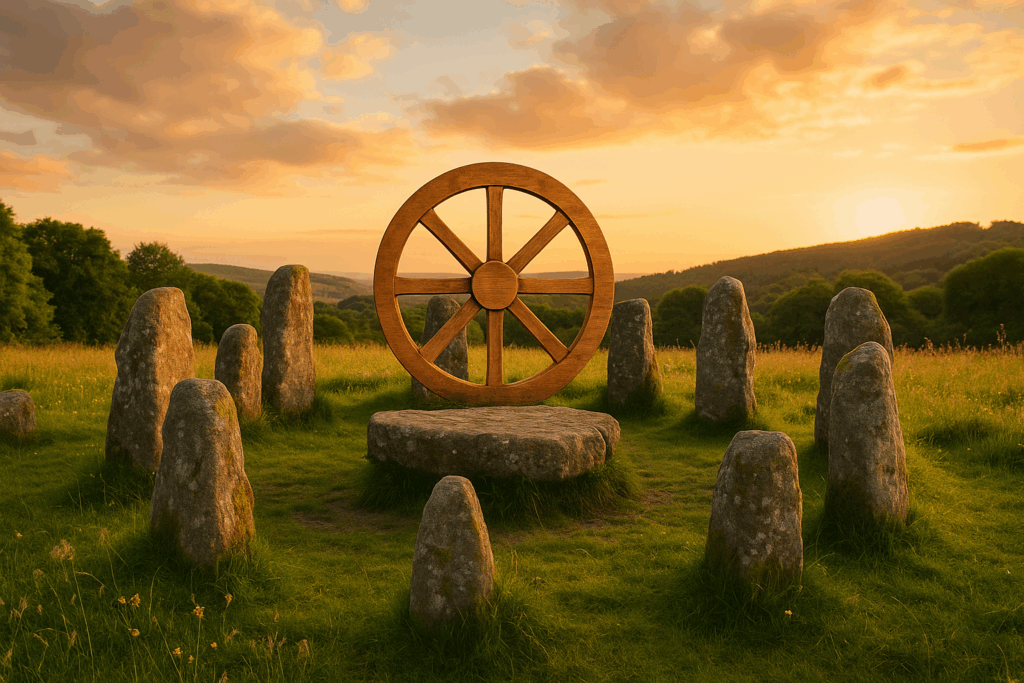

October 31 – The Feast of the Dead

Samhain proper — celebration of ancestors, fire, and the eternal cycle.

The final day of October is not simply a date — it is a turning of worlds. Samhain, the ancient festival that crowns the wheel of the year, is both an ending and a beginning. The harvest has been gathered, the fires are lit, and the night itself breathes with ancient presence. This is the hinge of time, the night when the veil is fully open and the living and the dead share one breath, one heartbeat, one flame. The Feast of the Dead is not a feast of sorrow but of connection — a sacred celebration of those who came before, of death as teacher, and of life as an eternal returning.

On this night, the old Celtic year ends. To the ancestors, it marked the death of the sun’s reign and the beginning of the dark half of the cycle. But the dark was never evil — it was the fertile mystery from which life would return. Bonfires were kindled on hilltops, their flames rising like beacons to guide spirits home and to protect the living from wandering shades. Hearth fires were extinguished, then relit from the communal flame, symbolizing renewal and shared life. The people feasted, not in fear of death, but in fellowship with it, knowing that life and death are threads woven into the same eternal fabric.

To celebrate Samhain today is to remember that rhythm — to honor endings not as loss, but as transformation. The Feast of the Dead is both remembrance and renewal, a moment to sit with your ancestors in gratitude, to feel the pulse of their wisdom moving quietly through your veins. Whether you practice alone or among friends, this is a night to step fully into the mystery, with open eyes and steady heart.

Begin your evening by cleansing and preparing your space. Open a window to let the old air drift away, then light candles or incense to welcome the new. If possible, build a fire outdoors or in a hearth — the ancient heart of Samhain. Fire is the bridge between worlds, transforming matter into spirit, darkness into light. As the flames rise, watch how they twist and dance, how their glow warms everything it touches. In this light, all divisions — between life and death, past and present, self and other — begin to dissolve.

Prepare your Feast of the Dead with intention. It can be as simple as bread, apples, and wine, or as elaborate as a full meal featuring seasonal foods — squash, root vegetables, nuts, and grains. Set one extra place at your table, a chair for those unseen who join you tonight. Upon the plate, lay a small portion of each dish, and beside it, a glass of water or wine. These offerings are the heart of the feast, gifts of hospitality for those whose footsteps echo in the earth beneath yours. Before you eat, take a moment of silence. Say:

“To those who walked before,

To those who walk unseen beside us,

We give thanks.

May you find peace in our remembrance,

And warmth in our hearth’s light.”

As you dine, keep awareness of your guests. You may feel subtle sensations — a flicker of warmth, the sense of company, a memory surfacing unbidden. The dead do not require grand rituals to appear; they respond to sincerity, to the quiet pulse of love. As you eat, speak softly to them. Tell them about the year gone by, about joys and struggles, about what you have learned. This conversation between worlds is the essence of the Feast — not mere ritual, but communion.

When the meal is finished, carry your offerings outdoors beneath the night sky. If you have a fire, place a small portion into it, watching the smoke rise. Whisper, “Take and be blessed.” If not, pour your offerings onto the earth or at the roots of a tree, returning nourishment to the soil. The act completes the cycle: what was taken from the land returns to it, sanctified by gratitude.

Afterward, you may wish to spend time in reflection or divination. Samhain is the witch’s new year, the perfect moment to seek guidance for the cycle ahead. Light a candle and draw tarot cards, cast runes, or simply gaze into a bowl of water or mirror. The messages you receive tonight are often clearer, closer, for the veil is open and the ancestors whisper easily. Write down what you see or feel — dreams, symbols, impressions — for they may carry meaning long after this night has passed.

If you practice with others, gather around a bonfire or circle of candles. Sing, drum, or tell stories of the dead — not just of their deaths, but of their lives, their humor, their humanity. Laughter is sacred here; joy honors them as much as tears. In the flicker of flame and the rhythm of voices, you will feel the presence of countless generations joining you, unseen but unmistakable. The Feast of the Dead is not somber — it is celebration, the soul’s recognition of continuity.

For solitary practitioners, the night may unfold more quietly but no less powerfully. Sit by candlelight and meditate on the cyclical nature of all things. Watch how the flame consumes itself to give light — how each spark, though fleeting, contributes to the eternal fire. In that reflection, see your own place in the great web of existence. Death is not the end of the story; it is the comma between chapters. The spirit does not vanish; it changes shape, waiting to return when the wheel turns again.

Before the night ends, it is traditional to perform a closing of the year ritual. Stand before your altar or fire and say:

“The year dies and is reborn.

The light fades, but will rise again.

As the earth sleeps, so too shall I dream.

What is remembered lives.”

Take a moment to name what you are ready to leave behind — griefs, fears, old patterns. Speak them aloud and imagine the fire consuming them, transforming their weight into warmth. Then, whisper a single word for what you wish to carry into the new year — peace, love, courage, truth. Let it rest in your heart like a glowing ember. It will guide you through the long winter to come.

When you finally extinguish your candles, do so in gratitude. The spirits will return to their realm as dawn approaches, but their blessings remain. Leave your altar undisturbed overnight if you can — let the energy of the feast linger. In the morning, you may clear it and bury the remnants of food as offerings to the earth.

As the night fades into November, remember that Samhain is not only about death — it is about the eternal spiral of existence. The same darkness that cradles the dead also cradles the unborn. The same silence that follows endings is the one from which new songs arise. The Feast of the Dead teaches us that life is never lost, only transformed — that we, too, will one day be the whisper in the leaves, the warmth in the fire, the breath in our descendants’ prayers.

So light your candles. Feast. Remember. The veil is open, and love moves freely between the worlds. Tonight, the living and the dead dine together, and all things — all beings — are one.